- Syllabus

- 1 Introduction

- 2 Data in Biology

- 3 Preliminaries

- 4 R Programming

- 4.1 Before you begin

- 4.2 Introduction

- 4.3 R Syntax Basics

- 4.4 Basic Types of Values

- 4.5 Data Structures

- 4.6 Logical Tests and Comparators

- 4.7 Functions

- 4.8 Iteration

- 4.9 Installing Packages

- 4.10 Saving and Loading R Data

- 4.11 Troubleshooting and Debugging

- 4.12 Coding Style and Conventions

- 4.12.1 Is my code correct?

- 4.12.2 Does my code follow the DRY principle?

- 4.12.3 Did I choose concise but descriptive variable and function names?

- 4.12.4 Did I use indentation and naming conventions consistently throughout my code?

- 4.12.5 Did I write comments, especially when what the code does is not obvious?

- 4.12.6 How easy would it be for someone else to understand my code?

- 4.12.7 Is my code easy to maintain/change?

- 4.12.8 The

stylerpackage

- 5 Data Wrangling

- 6 Data Science

- 7 Data Visualization

- 8 Biology & Bioinformatics

- 8.1 R in Biology

- 8.2 Biological Data Overview

- 8.3 Bioconductor

- 8.4 Microarrays

- 8.5 High Throughput Sequencing

- 8.6 Gene Identifiers

- 8.7 Gene Expression

- 8.7.1 Gene Expression Data in Bioconductor

- 8.7.2 Differential Expression Analysis

- 8.7.3 Microarray Gene Expression Data

- 8.7.4 Differential Expression: Microarrays (limma)

- 8.7.5 RNASeq

- 8.7.6 RNASeq Gene Expression Data

- 8.7.7 Filtering Counts

- 8.7.8 Count Distributions

- 8.7.9 Differential Expression: RNASeq

- 8.8 Gene Set Enrichment Analysis

- 8.9 Biological Networks .

- 9 EngineeRing

- 10 RShiny

- 11 Communicating with R

- 12 Contribution Guide

- Assignments

- Assignment Format

- Starting an Assignment

- Assignment 1

- Assignment 2

- Assignment 3

- Problem Statement

- Learning Objectives

- Skill List

- Background on Microarrays

- Background on Principal Component Analysis

- Marisa et al. Gene Expression Classification of Colon Cancer into Molecular Subtypes: Characterization, Validation, and Prognostic Value. PLoS Medicine, May 2013. PMID: 23700391

- Scaling data using R

scale() - Proportion of variance explained

- Plotting and visualization of PCA

- Hierarchical Clustering and Heatmaps

- References

- Assignment 4

- Assignment 5

- Problem Statement

- Learning Objectives

- Skill List

- DESeq2 Background

- Generating a counts matrix

- Prefiltering Counts matrix

- Median-of-ratios normalization

- DESeq2 preparation

- O’Meara et al. Transcriptional Reversion of Cardiac Myocyte Fate During Mammalian Cardiac Regeneration. Circ Res. Feb 2015. PMID: 25477501l

- 1. Reading and subsetting the data from verse_counts.tsv and sample_metadata.csv

- 2. Running DESeq2

- 3. Annotating results to construct a labeled volcano plot

- 4. Diagnostic plot of the raw p-values for all genes

- 5. Plotting the LogFoldChanges for differentially expressed genes

- The choice of FDR cutoff depends on cost

- 6. Plotting the normalized counts of differentially expressed genes

- 7. Volcano Plot to visualize differential expression results

- 8. Running fgsea vignette

- 9. Plotting the top ten positive NES and top ten negative NES pathways

- References

- Assignment 6

- Assignment 7

- Appendix

- A Class Outlines

11.1 RMarkdown & knitr

A markup language is a special kind of programming language used to annotate and decorate plain text with information about its intended formatting and structure. The syntax of a markup language is intended to be easy to read and write by humans and also machine readable, so that it may be processed by formatting programs into different formats, e.g. the same markup text might be converted into HTML or PDF.

markdown is one such markup language. The markup is simple, and provides basic formatting syntax by default. The following contains some examples of markdown syntax:

You can *emphasize* text, or **really emphasize it**. Lists are pretty easy to

read as well:

* item 1

* item 2

* item 3

If you need an enumerated list you can do that too:

1. item 1

2. item 2

3. item 3

You can easily include links to web sites like [Google](http://google.com) and

images:

{width=50%}The markdown from above might be formatted as follows:

You can emphasize text, or really emphasize it. Lists are pretty easy to read as well:

- item 1

- item 2

- item 3

If you need an enumerated list you can do that too:

- item 1

- item 2

- item 3

You can easily include links to web sites like Google and images:

an image of a master of the universe

Refer to the markdown documentation for a complete listing of supported markdown syntax.

Some other markup languages you might recognize:

- ReStructured Text - the markup language used in most python documentation

- LaTeX - a markup language designed to help format mathematical expression

- HTML - the web markup language (HyperText Markup Language)

- wikitext - the markup language used by Wikipedia

As the name suggests, RMarkdown is

an extension of markdown that works in R. The most important extension is the

ability to include code blocks in R in between markdown formatted text that can

be executed. This enables writing executable reports that update their results

whenever the document is rerun interspersed with explanatory text and other

descriptive elements. For this reason, RMarkdown files are sometimes called

RMarkdown notebooks, because they can be used to record both narrative text

and results, similar to a traditional lab

notebook. RMarkdown files typically

end with .Rmd.

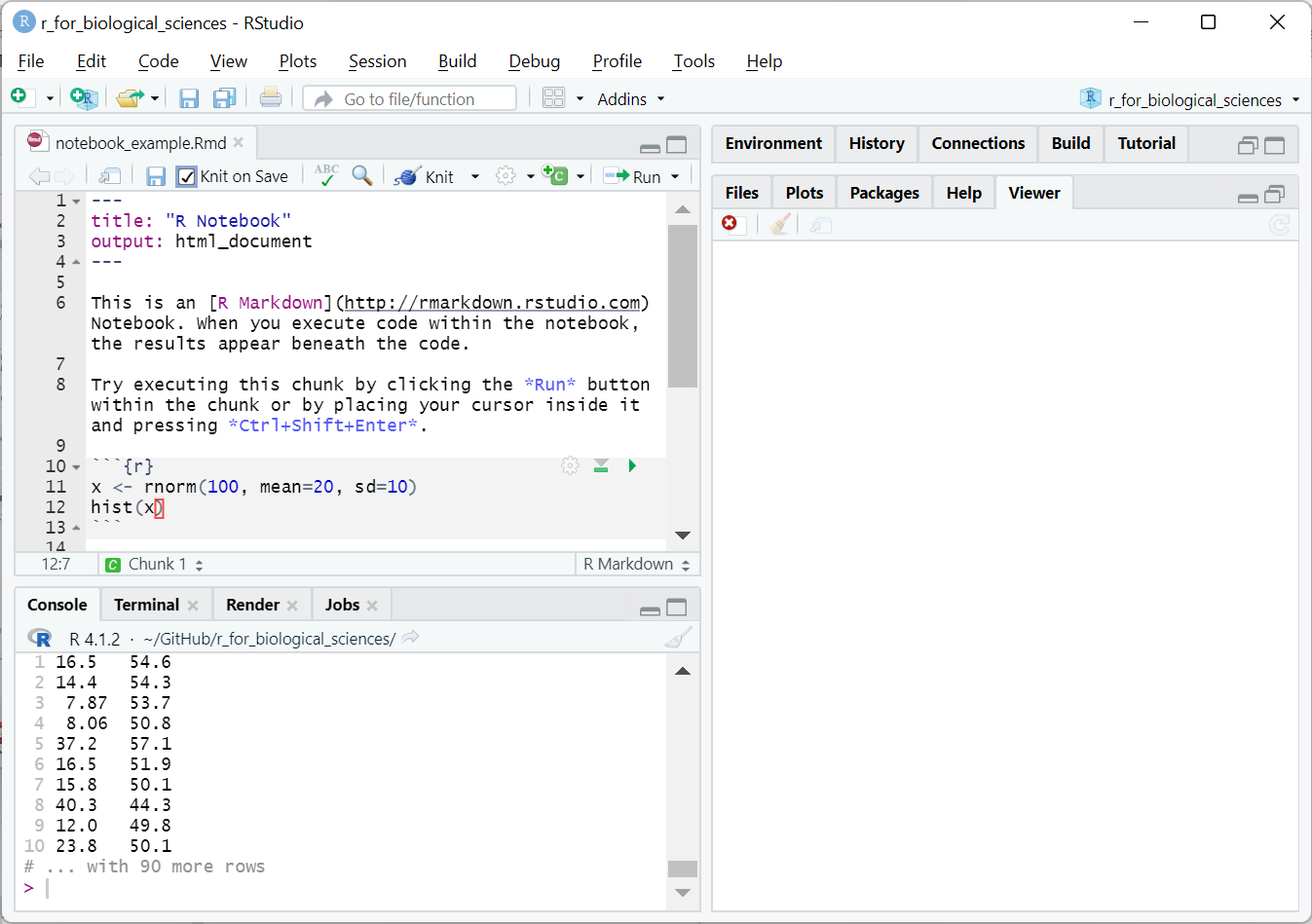

RStudio has full RMarkdown integration to make writing RMarkdown notebooks very easy. Below is a screenshot of an RMarkdown document loaded in RStudio:

RMarkdown notebook example

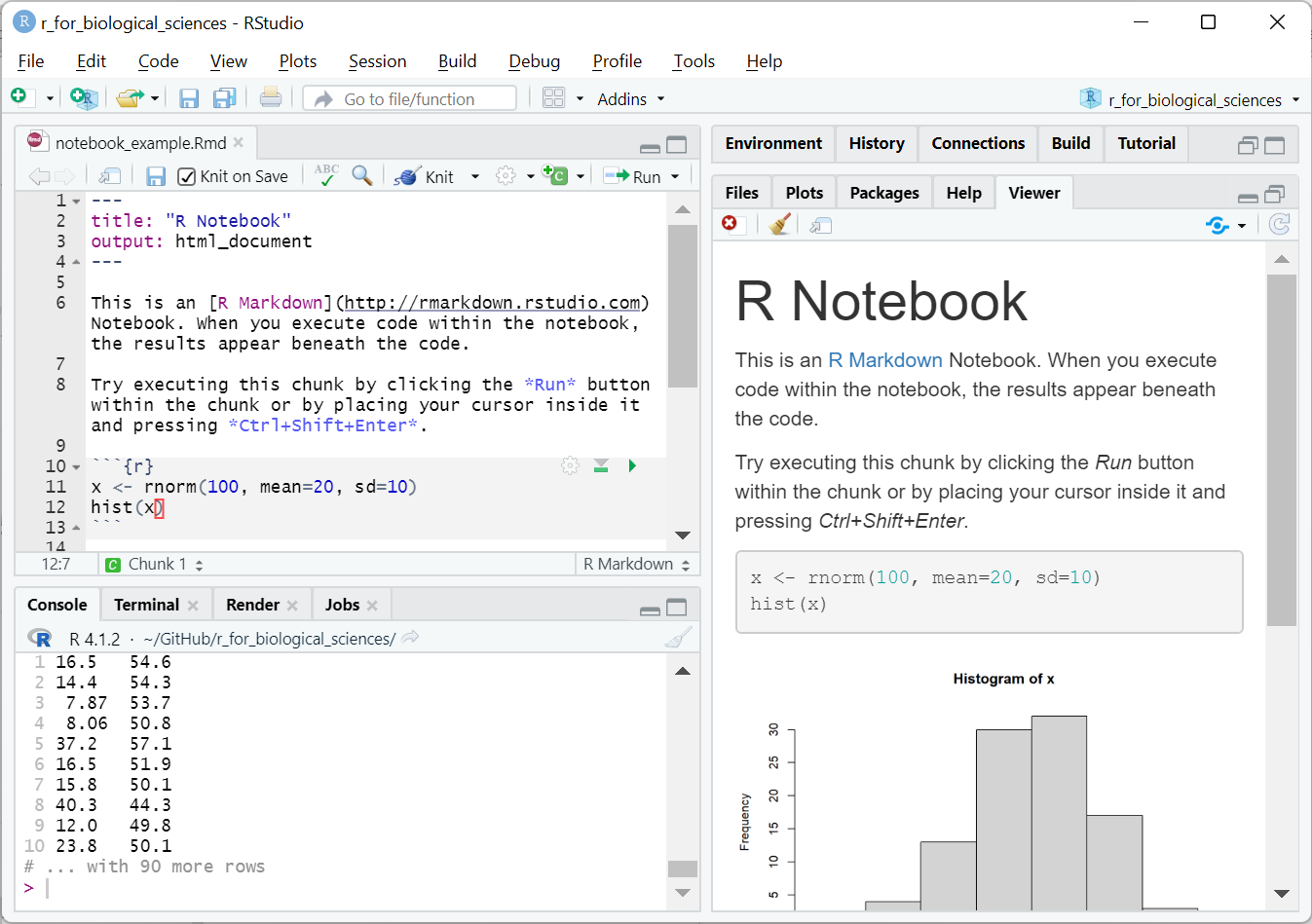

The grey lines starting with ```{r} define a special code

block that contains R code that should be executed and the output placed after

the block. When run, RStudio will show you the output of the notebook within its

interface:

RMarkdown notebook example after running

Notice how there is now a plot in the rendered document on the right. The code within the block was run, the plot generated, and inserted into the report. In this case, the notebook created an HTML document that RStudio knows how to display, but could also be opened in a standard web browser.

These blocks are not standard R syntax, but are instead understood and processed by the knitr R package. As the name suggests, the process of generating a report from an RMarkdown document is called “knitting”; you would ask RStudio to knit your RMarkdown into a report.

RMarkdown documents can be knitted into many different formats, including HTML, PDF, Microsoft Word, and even some slide presentation formats. When exporting to HTML, the report may include interactive elements including plots, collapsible sections, and code blocks, and maps.

RMarkdown documents can also be written to accept parameters. This means you can write a single RMarkdown document that can be run on different inputs. Reports for standardized analytical pipelines, as are often implemented by high throughput sequencing cores, can thus be generated trivially for new datasets as they are generated without writing any additional code.